La musique pop était-elle initialement une échappatoire à cette dynamique familiale d'isolement et de claustrophobie ? "Non, c'était plus ce qu'on appelle en France un coup de foudre dans tous les sens du terme. C'était inattendu et ce fut l'amour au premier regard. » Elle raconte comment sa mère fit pression sur son père absent pour lui acheter un cadeau en récompense de sa réussite au baccalauréat [le diplôme d'école française]. "J'étais plus jeune que n'importe quel élève de mon année et pourtant j'ai réussi à obtenir les meilleures notes." A l'adolescence, elle était "obsédée" par Radio Luxembourg, écoutant tous les soirs les chansons pop venues de Grande-Bretagne et d'Amérique, sous le charme des stars de l'ère d'avant les Beatles : Elvis, Brenda Lee, Rosemary Clooney, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury et Cliff Richard. "Je ne saurai jamais pourquoi j'ai choisi une guitare parce qu'une radio à transistor était tout ce que je voulais", dit-elle, toujours perplexe. "De plus, je ne connaissais absolument rien sur la façon de jouer de la guitare, alors j'ai été stupéfaite de constater que je pouvais faire tellement de choses à partir de trois accords." Elle a commencé à écrire des chansons avec obsession dans sa chambre, parfois trois ou quatre par semaine. "Vraiment, ces trois accords sont à l'origine de la plupart de mes chansons des 10 années suivantes."

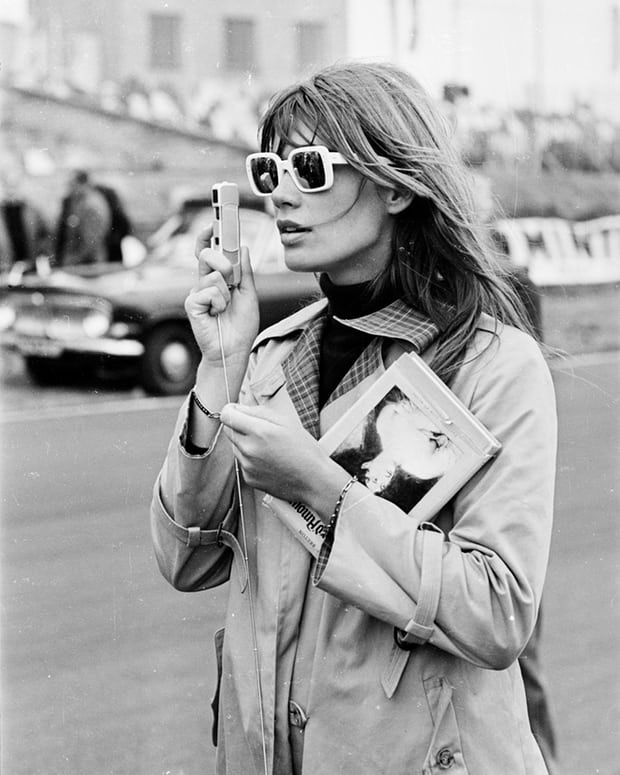

Francoise Hardy à Brands Hatch pendant le tournage du film de John Frankenheimer de 1966 Grand Prix. Photographe : Victor Blackman/Getty Images

Malgré sa timidité aiguë et son manque de confiance en elle, elle a voulu participer à une audition publique organisée par Pathé Marconi, alors premier label de musique en France. "C'est difficile à expliquer," dit-elle en fronçant les sourcils, "mais même si je ne pensais pas que j'étais très douée, j'avais besoin d'une confirmation. J'avais besoin qu'on me dise que je devais abandonner. Aussi, je savais que si je ne saisissais pas cette opportunité, aussi humiliante que soit le résultat, je le regretterais pour le reste de ma vie. C'est vraiment comme ça que j'ai trouvé le courage d'y aller. "

L'audition n'a pas été un succès, mais cela n'a pas non plus été l'échec qu'elle avait anticipé - «Je suis partie tellement heureuse de ne pas avoir été refoulée rapidement.» Elle a persévéré et a participé à d'autres auditions organisées par le label Vogue. Sa première session d’enregistrement en studio dura moins de quatre heures et produisit cinq chansons totalement terminées. À sa grande horreur, le label a choisi la chanson pop légère, Oh oh chéri, composée par l'équipe de Johnny Hallyday, comme face A de son premier single. Mais c'est à sa propre composition, Tous les garçons et les filles, que les stations de radio et le public ont été réceptifs. Sorti en 1962, il s'est vendu à 2 millions d'exemplaires en France et en Grande-Bretagne il n'a tout juste pas réussi à se classer parmi les 20 premiers. Soudainement, âgée de 18 ans et toujours une écolière timide, Hardy devint la plus grande pop star de France. "J'ai écouté ce disque et j'ai été très insatisfaite," dit-elle, "et j'ai été très souvent insatisfaite après."

Texte original :

Her otherness, Hardy says, began in childhood. Born in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1944, her early years were marked by an absent, emotionally withdrawn father, and a mother who, she says, “lived the life of a nun”. In the immediate postwar years, after her parents’ separation, her mother worked long hours to pay for her daughter’s convent education. “My mother was a solitary figure who did not really have any friends,” she tells me, matter-of-factly. “At the weekends, my sister and I were sent to my grandparents’ house and that was it. The atmosphere was so strict and there was a lot of shame perhaps to do with my parents’ separation. My grandmother told me repeatedly that I was unattractive and a very bad person, which makes you think as a child that you will never meet anyone. It is hard even now for me to understand why she was like that.”

Was pop music initially an escape from that cloistered, claustrophobic family dynamic? “No, it was more what we call in France a coup de foudre [thunderbolt] in every sense of the word. It was unexpected and it was love at first sight.” She recounts how her mother pressurised her absent father to buy her a gift as a reward for excelling at the baccalaureate [the French school diploma]. “I was younger than any pupil in my year and yet I somehow achieved the highest marks.” At that time, in her mid-teens, she was “obsessed” with Radio Luxembourg, listening nightly to the pop songs it broadcast from Britain and America, in thrall to the stars of the pre-Beatles era: Elvis, Brenda Lee, Rosemary Clooney, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury and Cliff Richard. “I will never know why I chose a guitar because a transistor radio was all I ever wanted,” she says, still looking perplexed. “Plus, I knew absolutely nothing about how to play the guitar, so I was astonished to find that I could make so much from just three chords.” She began writing songs obsessively in her bedroom, sometimes knocking out three or four in a week. “Really, those three chords produced most of my songs for the next 10 years.”

Despite her acute shyness and lack of confidence, she willed herself to attend an open audition hosted by Pathé Marconi, then France’s premier record label. “It’s difficult to explain,” she says, frowning, “but even though I did not think I was very good, I somehow needed to have that confirmed. I needed to be told that I should give up. Also, I knew that if I did not take this chance, however humiliating the result might be, that I would regret it for the rest of my life. That is really how I found the courage to go.”

The audition was not a success, but neither was it the failure she anticipated – “I left feeling so happy that I had not been thrown out quickly.” She persevered, attending other auditions and soon afterwards, in 1961, she was offered a contract by the Disques Vogue record label. Her initial studio session lasted less than four hours and produced five finished songs. To her horror, the label chose a lightweight pop confection, Oh oh chéri, composed by Johnny Hallyday’s songwriting team, as the A-side of her debut single. But it was her self-penned song, Tous les garçons et les filles, that the radio stations and the public responded to. Released in 1962, it sold 2m copies in France and in Britain it just failed to make the top 20. Suddenly, aged 18 and still a shy convent schoolgirl at heart, Hardy became France’s biggest pop star. “I listened to that record and I was so dissatisfied,” she says, “and I have been dissatisfied very often ever since.”

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire